MARCELLO NIZZOLI

1887 - 1969

MARCELLO NIZZOLI

Whilst Marcello Nizzoli is best known as the product designer responsible for some of Olivetti’s most celebrated machines, he considered himself first and foremost an artist. As a young man he studied art at Scuola die Belle Arti in Parma, where his interest in Cubism and Futurism was born. Cubism, an artistic movement popularized by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, marked a revolutionary break from Renaissance-era realism and religious themes. Cubist paintings were fragmented, geometric and abstract – or as Picasso put it - ‘A head, is a matter of eyes, nose, mouth, which can be distributed in any way you like’.

Closer to home, Nizzoli was heavily influenced by Italian Futurism - particularly the work of Fortunato Depero – which borrowed the detached forms and reactionary spirit of Cubism, yet differed in its subject matter. Italian Futurism aspired to break all links with the past and instead praise the power of modernity - depicting the glory of automobiles, steamships, tanks and machines. There was, however, a dark side to Italian Futurism. The movement was fundamentally intwined with the glorification of war, nationalism, and technology - framing conflict as a powerful, purifying force essential to progress. Broadly, the movement embraced a fervent, aggressive patriotism that advocated for Italy to assert its power through violence.

It was at this time, in 1913, that Marcello Nizzoli graduated University – and began his work as a professional painter. Italian Futurism was in vogue, and as his exhibitions garnered widespread critical acclaim in Milan. Yet within months of his personal success Germany had begun its expansion across Europe – and war was formally declared in August of 1914. Italian men were to be conscripted – and Marcello Nizzoli was forced to grapple with the knowledge that the very art movement he ascribed to – one that celebrated the destructive power of modern warfare – may lead to his untimely death.

And whilst many of Marcello’s peers were to die, Nizzoli survived by twist of fate. On the eve of his deployment, Marcello Nizzoli’s father suddenly died. The Nizzoli family owned a successful steelworks factory in Cornigliano which fabricated ammunition, vehicles, and tanks for the Italian Army - and thus Nizzoli was excused from compulsory service. Returning to run the business for the duration of the war, he was still determined to exercise his artistic talents. It was at this time that Nizzoli designed advertising illustrations for war effort. His graphic designs gained notoriety, and soon Nizzoli was asked to illustrate posters for famous Italian companies Campari, Martini and Maga.

Like many futurist artists of the period, Nizzoli also designed commercial posters for the emerging fascist government Fasci Italiani di Combattimento. It is difficult to determine whether Nizzoli was himself supportive of Mussolini’s regime – or if his artwork was simply bound by the political confines of the time. In any case, in the post war period Nizzoli distanced himself from futurism - and began work in interior and furniture design. It was during this time that the Italian Rationalism design movement emerged. Rationalism was a synthesis of tradition – employing the classical architectural features of Ancient Rome – and modernism – in its use of scale, geometry and modern materials. Rationalism was both a major fascist propaganda tool that sought to impose strength and power, yet at the same time was a genuine search for a new artistic identity.

Despite Rationalism being the official art of the Fascist state, its use by Marcello Nizzoli was patently subversive. In 1930 he collaborated with Luciano Baldessari and Guiseppe Terrangi to build the iconic Craja coffee bar in Milan. The bar was intended as a laboratory of revolutionary ideas – akin to the Café de Foy – at great risk to the patrons under the totalitarian regime. Aesthetically, it was unlike any other café in the city. There was no wooden panelling, gilded stuccos, mirrors and comfortable armchairs - instead it was angular, made from sheet aluminium and completely lacking in adornment. The café can be understood as a Rationalist rebellion and was a meeting place for architects, poets, artists, and writers who resisted the regime.

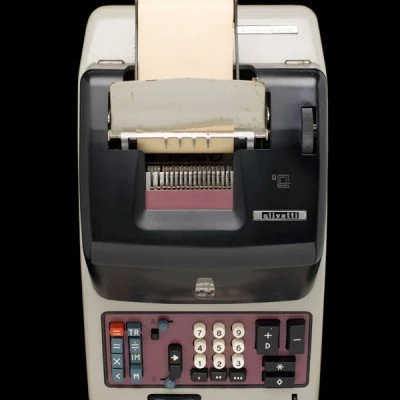

It was in this café in 1938 that Marcello Nizzoli met the person who had the most influence over his career – the manufacturer Adriano Olivetti. Nizzoli worked first for Olivetti as a consultant, and was soon after promoted to designer. His first project, MC 4S Summa, was a sleek desktop calculator created in the Olivetti planning and research office. Unlike other models of the time, deep consideration was given to technical, ergonomic and aesthetic aspects of the product. As at Olivetti, aesthetics were given the same weight as the technical aspects of a design. It paid off and from here Marcello Nizzoli created some of the most celebrated designs to come from Olivetti – including the Lexikon 80 (1945) the Divisumma 14 (1946) and the Leterra 22 (1952). He went on to design numerous architectural projects for Olivetti, before illness caused his early retirement and death. Today, the legacy of Marcello Nizzoli is one of widespread artistic merit, industrial design influence and the difficulties of existing in the grey area between alignment and resistance.

KEY DESIGNS:

Olivetti Lexicon 80 typewriter (1948): A well-known design that marked a significant contribution to the company's innovative approach to office equipment.

Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter (1950): An iconic portable typewriter that received the inaugural Compasso d'Oro award in 1954 for its design.

Olivetti Divisumma 14 printing calculator (1947): A key product in Nizzoli's long-standing collaboration with Olivetti.

Necchi Mirella sewing machine (1957): A highly-regarded design for the Necchi company, which earned Nizzoli a second Compasso d'Oro award in 1957.

Aurora 88 fountain pen (1948): Another of his iconic designs, showcasing his versatility beyond office machines.

Mirella Sewing Machine (1957): This design won Nizzoli his second Compasso d'Oro award in 1957.

OAurora 88 Fountain Pen (1948): An iconic design in the realm of writing instruments.

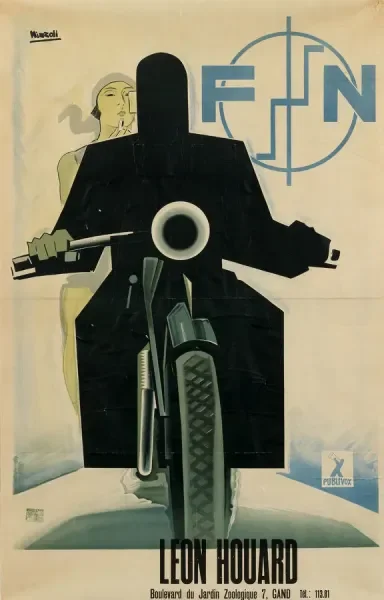

FN (Fabrique Nationale): Created in 1925. The design, which features a phantom-like motorcycle rider, emphasizes power and style and uses a dynamic composition with dramatic angles.

Campari, l'apéritif (Campari, the aperitif): Designed in 1926. This rare and large poster is in the Art Deco style and features a bottle of Campari, a glass, and a blue cocktail soda spray bottle.

Cordial Campari Liquor: An original vintage poster from 1927.

Motosacoche: Nizzoli designed several posters for the Swiss motorcycle company, including some in 1927 and circa 1927.

Pastilles Riza: Created in 1927.

E.I.A.R. Ente Italiano Audizioni Radiofoniche: A lithograph poster designed between 1928-1930.

Architecture: He was involved in several architectural projects, including living quarters and office buildings for Olivetti employees and the ENI office block in San Donato Milanese (1956–58).

COLLABORATIONS:

Olivetti: This was Nizzoli's most significant and enduring professional relationship. He first joined in 1938 as a graphic designer and later became the chief consultant for product design. His work for Olivetti defined modern Italian industrial design, creating iconic products like the Lettera 22 typewriter and Divisumma calculators. He also designed employee living quarters and office buildings for the company.

Necchi: Nizzoli designed several successful sewing machines for this Italian company, most notably the Mirella, which won a second Compasso d'Oro award in 1957.

Aurora: He collaborated with the writing instrument company Aurora to design the iconic Aurora 88 fountain pen in 1948.

Campari / Martini / Motosacoche: Early in his career, Nizzoli worked extensively as a graphic designer, creating famous poster advertisements for brands like Campari and Martini, and the Swiss motorcycle company Motosacoche.

Giancarlo Palanti: They co-designed the Salone d'Onore at the Triennale of 1936 in Milan.

Studio Nizzoli Associati: A design studio founded in 1965, continuing his legacy and collaborating with brands like Stilnovo

Matteograssi: Bartoli collaborated with Matteograssi to produce dining chairs and other pieces, such as the Vela

Rossi di Albizzate: For Rossi di Albizzate, Bartoli developed the modular Blob sofa and the award-winning Tube sofa.

Segis: This partnership yielded multiple award-winning products, including the R606 UNO chair (with Fauciglietti Engineering) and the Breeze stacking armchair.

Tisettanta: Collaborations with Tisettanta led to designs such as the Mito table.

Giuseppe Beccio: Nizzoli worked alongside the engineer Giuseppe Beccio in the Olivetti planning and research office to ensure a harmonious blend of aesthetics and functional engineering in products like the Lettera 22. This collaboration between artist and technician was fundamental to Olivetti's design philosophy.

G. M. Oliveri: He collaborated on architectural projects with G. M. Oliveri, including the design of the ENI office block in San Donato Milanese, Milan, in the late 1950s.

Edoardo Persico: Persico's influence in the early 1930s was important in shaping Nizzoli's architectural approach and his work toward integrating the arts with architecture.

FURTHER READING:

Art Directory, (n.d.). Marcello Nizzoli. http://www.marcello-nizzoli.com/

Mangone, F., (2013). Marcello Nizzoli. Biographical Dictionary of Italians. http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/marcello-nizzoli_(Dizionario-Biografico)/

Art, Fascism and War (2009) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230013884_Art_Nationalism_and_War_Political_Futurism_in_Italy_1909-1944