VICO MAGISTRETTI

1917 - 2007

VICO MAGISTRETTI

Vico Magistretti spent his entire career in a studio at the corner of Via Conservatorio and Via Vincenzo Bellini in Milan. It was a small studio, modest in size: barely eighty square metres on the ground floor, made up of three small rooms (one, a jumbled archive of designs piled high enough to touch the ceiling) and a very basic bathroom (with no hot water until 2010).

This makes perfect sense for this homebody architect, town planner, designer and academic; and it is often said that Vico Magistretti is the designer for the home. To understand his deep reverie for the safety of this most sacred place, one must look at the context in which he grew up. Born in 1920, he was a young man when the allied bombings of World War II destroyed Milan in 1945. In the immediate years after the conflict the Italian government financed anonymous and impersonal buildings reflecting a uniform loneliness and identity loss felt by the Milanese. People who had left the city were starting to move back, but they had nowhere to go. So, the idea of “home” became powerful and aspirational, particularly in work of Vico Magistretti.

Magistretti never trained as a designer, and had an unorthodox approach to design. It is said that he would scribble ideas on scraps of paper, or on the back of bus tickets, before taking them through the final stages of production. Magistretti was not bound to the confines of traditional design ideas, and instead followed a simple principle: a good design was one that could adapt to any taste, need, and space. It is precisely this aptitude democratic design solutions that led him to succeed in creating iconic home objects for the middle-class.

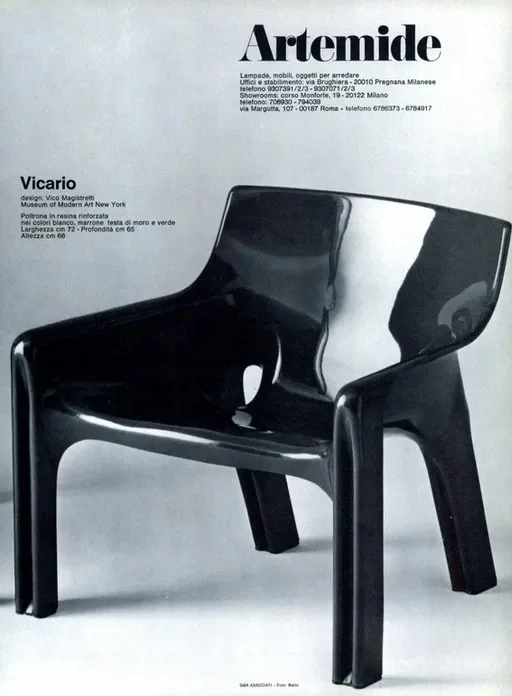

Just as Magistretti did not operate under traditional design constraints, he also was not constricted by traditional materials. As the space race waged between Soviet Russia and the U.S.A in the 1960s, the world saw rapid technological advances. One new material was injection moulded fibreglass, (strong, lightweight material resistant to heat) that became the material of choice for space suits. In 1969 Magistretti adopted this technique into his design practice by creating the Selene chair - made entirely from a single sheet of thermo-moulded resin. It is considered a revolutionary moment in Italian and international design - the first of its kind to be replicated for decades to come.

Despite his extraordinary success and the multitude of awards as a designer, in the ’60s Magistretti returned to his first love - architecture. Along with his close friend Luigi Caccia Dominioni, they created Milan San Felice, an out-of-town, middle-class neighborhood. His houses stood as triumphs of his philosophy, in their way of being conceived as objects generated by the priority of human experience. Magistretti would describe this principle in 1993, “never mind if they’re lovely or ugly, but structured. they’re inhabited in the right way” (Gli arredi degli architetti, Domus 748, April 1993). His architecture was much like his furniture - an expression of an era - wherein the experience of enjoying one’s own space, where people can relax or be welcomed were the foundation of all high-end domestic living concepts. He was all about creating buildings and furniture where, in different ways and scales of association, the ritual of dwelling was celebrated, be it for a family or for a whole citizenry.

KEY DESIGNS:

Eclisse Table Lamp (1967) for Artemide: A sculptural and functional table lamp, the Eclisse has a rotating inner globe that allows the user to adjust the light from direct to diffused. The design won the Compasso d'Oro award in 1967.

Atollo Table Lamp (1977) for Oluce: Inspired by simple geometric shapes, the Atollo table lamp is composed of a conical base, a cylinder, and a hemispherical shade. This iconic lamp also won the Compasso d'Oro award in 1979.

Sonora Pendant Lamp (1976) for Oluce: The Sonora is a large, elegant pendant lamp that uses geometric shapes to create a minimalist yet striking impression.

Dalù Table Lamp (1966) for Artemide: This re-edition of a 1960s classic has a modern, continuous form with a distinctive curved shape, translating the aesthetic of the 1960s into a contemporary design.

Chimera Lamp (1969) for Artemide: A serpentine table lamp made from opaline methacrylate, the Chimera provides diffused, atmospheric lighting.

Signature furniture

Maralunga Sofa (1973) for Cassina: Designed for comfort, the Maralunga sofa is notable for its innovative, individually adjustable, and folding backrests. The design won Magistretti a Compasso d'Oro in 1979.

Nuvola Rossa Bookcase (1977) for Cassina: An international bestseller, this bookshelf is composed of hinged wooden frames that create a ladder-like structure. The simple design has often been imitated.

Carimate Chair (1959) for Cassina: This chair is known for its elegant red-painted wooden frame and rush seating, which reflects a blend of modern and traditional Italian design.

Selene Chair (1968) for Artemide: One of the first successful experiments in mass-produced plastic seating, the Selene is a stackable, all-plastic chair with simple, flowing lines.

Veranda Sofa (1983) for Cassina: A modular, three-dimensional sofa with a focus on functionality and adaptability, the Veranda can be adjusted to different positions for a variety of seating arrangements.

Vidun Table (1987) for De Padova: This dining table features a unique, oversized screw mechanism that allows the height to be easily adjusted.